American Fiction: A film about not being about race

American Fiction: One size fits all?

Stereotyping sells. It’s a harsh truth that modern racism is still present in the media we consume all the time, internalised or blatant. Marketing race is not new, nor is it something consumers have really been critical of. It’s always a big deal when a novelist like R. F. Kuang releases a book like Yellowface because that’s easy to market: a young Asian-American author writes a novel about a white woman stealing an Asian-American competitor’s unpublished manuscript and publishing it as her own work. The premise is shocking, but it’s unsubtle.

Why does race have to figure so prominently in book and media marketing? And does it have to be that way? Is it truly a good thing to promote and laud creatives whilst placing their race front and centre, as if race is a determining factor which trumps all others? When the first Black Panther film was released in 2018, one of its main selling points was that it had a predominantly black cast and was concerned with a technologically advanced African empire entirely separate from the rest of the (white American) world. If we really want race to no longer be a factor that leads people to be discriminated against, surely we need to discard it altogether? Or would discarding it erase the history of injustice and struggle which some have faced in a racist society? It seems we cannot have racism without racial difference or at least racial labels, but we also can’t have race without someone somewhere believing that one race might be superior to another. We really are stuck between a rock and a hard place.

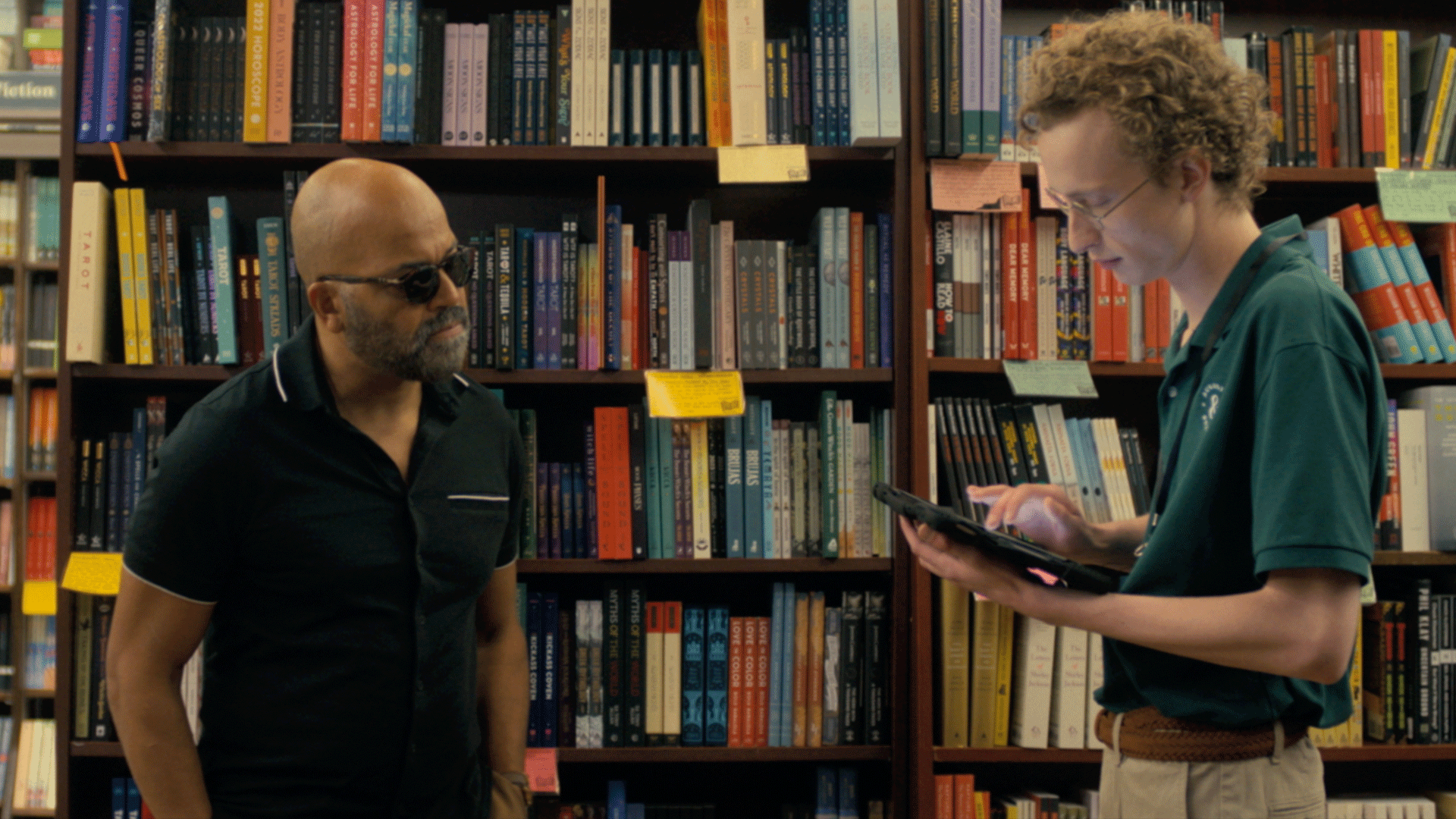

The very fact that American Fiction is marketed as a comedy also reveals something about how we deal with these issues. Are we incapable of having serious conversations about how we deal with race? I don’t necessarily think that’s true. Films like Jordan Peele’s Get Out famously took the horror genre previously dominated by white creatives and created a film which addressed historical racial injustices in a way that really stunned audiences. Satire always has an element of truth and seriousness along with comedy and irreverence - that combination is what makes stories like these so compelling. There’s certainly an appeal to the Americanness of the story and its characters. Monk believes his stories have nothing to do with race, and indeed that race does not exist.

The interplay between Monk and the female black novelist Sintara Golden is also very interesting because it’s not at all straightforward. It begins looking like there are very clear sides to take when we’re introduced to Golden from Monk’s scathing and disdainful perspective, but watching them directly interact on screen, the inescapability of their shared humanity (if not of shared experiences) makes for some tense and complex conversations. Monk’s award-winning manuscript is a joke which explodes beyond proportion, but the way it runs away from him once he takes it to his publisher reveals the extremity of the issue in hyperbolic terms. How far do these expectations go, and how much do they depend on essentially racist stereotypes? Never mind that Monk never intended the manuscript to be a serious literary work - it is utterly baseless fiction, conjured by a slightly drunk Monk angry at the world one evening. When Monk critiques Golden’s novel by saying it’s unrepresentative and undignified, her defence is that she did her research and the result is a novel which represents those subjects. The point of tension, then, is how to decide who gets to tell stories, what those stories are, and how they can possibly “represent” a whole group of people. All the characters in American Fiction lead very different lives, and have different experiences and opinions, therefore none of them can truly replace one another.

So what is this film actually trying to say? It satirises both the rejection of race as a concept and also the compartmentalisation of African-American stories to appeal to “popular” interests in the book and film markets. Is the film’s own ethics somewhere between these two? It does make a concerted effort not to make Monk’s life revolve around issues of race by presenting his concerns about his family, relationships and work at the forefront of the story rather than making explicit political statements. But perhaps that is the statement itself, and that would certainly line up with Monk’s ethics.

Knowing the answers to all the questions is not the point. It’s about being able to ask the questions in the first place, actually listening to the answers, suggestions, opinions, and the subsequent questions which arise. These are conversations that need to be had, but I’m just not sure any of us really know how to go about having them. Perhaps it can start with: “What did you think of American Fiction?”

Comments

Post a Comment