Studio Ghibli's environmental activism: Ponyo and Princess Mononoke

Ponyo and Princess Mononoke: Studio Ghibli’s environmentalism

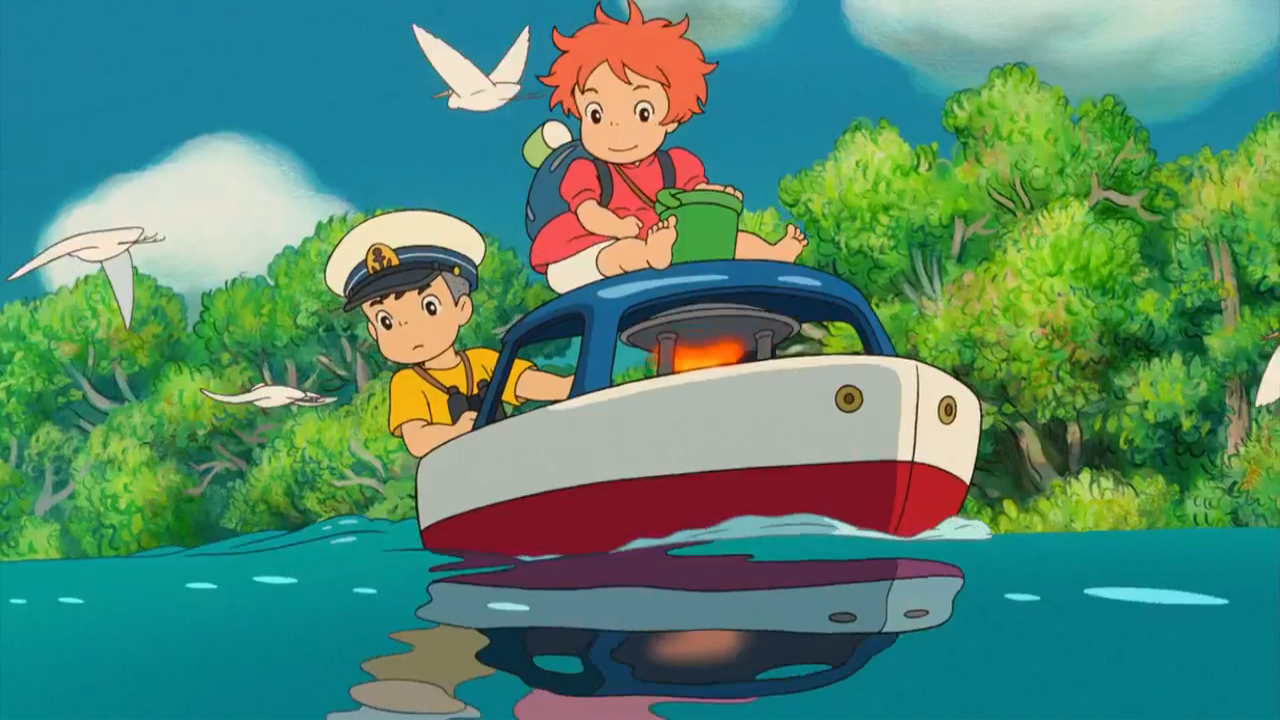

The environmental message of Studio Ghibli’s Ponyo (2008) and Princess Mononoke (1997) comes in large part from the visual and aesthetic emphasis placed on depicting nature in all its beauty, but there are also important messages about humans and our relationship with the natural world expressed through the films’ characters.

The collision of human and non-human worlds in these films isn’t throwing life into disrepair but into productive chaos. If not for the encounter between the characters, there would be no message to convey at all because quite simply nothing will have happened. Nature isn’t something to be feared or vilified into a threat when in reality the relationship between humans and the environment is highly complex. Even as I write this the words “environment,” “nature,” and “human” become increasingly unclear, undefined, and indistinguishable.

Ponyo is a character who occupies both human and non-human identities and it’s through her experiences with humans that audiences can begin to re-evaluate their own relationships with the environment, nature, and what they define as human or humanity. The ending of the film - Sosuke’s commitment to Ponyo - is itself a poignant metaphor for how we might want to approach environmentalism. As humans, we are in a position where we can do something about environmental crisis, particularly since most of the damage has been caused by humans in the first place. In some ways, the ending of Ponyo feels like a more optimistic revision of the message of Princess Mononoke’s conclusion.

In Princess Mononoke, San ultimately cannot forgive the human race for their role in the destruction of the natural world, and in turn cuts off her relationship with Ashitaka. I think it’s worth sitting in the complicated emotions of this moment in the film. San’s rejection of humanity for their actions can’t really be faulted, because it’s true both in the story and in the real world that humans have been responsible for extreme changes to the natural world. When she rejects humanity, do we as the audience feel particularly upset and even threatened by her choice because we feel that she rejects us personally? Is that because we don’t associate ourselves with the damage done to the natural world by humans more widely, or because we feel that a mirror has been held up to us to confront our part in it? San is a human raised by the she-wolf Moro, who lives in an intersection between the human and non-human which we might find difficult to understand. What does it mean for her to reject us, when San herself feels somewhat non-human? Indeed, what might it mean for humans to be rejected by the natural world, when for so long we have assumed that humans are the only beings with any power to dictate the state of the world, disregarding the fact that we depend on the natural world in order to exist? These are questions I’m not sure I have answers to, but the important part is that we ask them at all.

Aside from being visually beautiful films in their own right, Ponyo and Princess Mononoke are powerful examples of why art is deeply connected to the issues its audiences confront in their lives, and how art can be a truly productive tool in opening up conversations and new ways of thinking and imagining life for ourselves. It’s clear that their tones are very different, despite some shared themes and messages, but those differences can and should be productive. Dialogue about issues like environmental crises which concern not just individuals but quite literally the entire world need to take into account a range of voices, opinions, and perspectives. If one film studio can produce these two films which appear so different to each other but still find common ground, why can we not do the same in our own conversations?

Comments

Post a Comment