Disney's Robin Hood: why animals?

Robin Hood: animals and morality

A couple of weeks ago I wrote a blog on Wes Anderson’s adaptation of Roald Dahl’s classic children’s story Fantastic Mr Fox, and clearly I’m sticking to a theme so this week we’re having a look at Disney’s 1973 film Robin Hood.

First of all, why foxes? Or more broadly speaking, why animals? On a very basic level, the story of Robin Hood is based on legend anyway so why not take the extra creative leap and use animal characters when reimagining the story, especially if it can be more entertaining and accessible to young audiences.

The use of animals and anthropomorphism is actually a highly effective way of bringing young audiences closer to the story and characters. If the characters were human, audiences may not find the story as engaging because of the element of realism and seriousness, whereas animal characters create a wondrous new imagining of the Robin Hood legend which is whimsical and fun. Animal symbolism plays an important part in character design and the establishment of a moral tale since there’s a clear distinction between antagonists and protagonists. In the interest of not overcomplicating things, the primary split is between predator and prey or domesticable animals. Prince John, Sir Hiss, the Sheriff and his henchmen consist of a lion, a snake, a wolf, and two vultures respectively, and the local community include rabbits, mice, badgers, tortoises, and chickens, to name a few. Families and romantic partnerships are made visually decipherable through animal species; Maid Marian and Robin Hood’s romance is established before we hear the story of their early romance or see them on screen together, and so audiences can enjoy the certainty of their happy ending without concern - the tension can be built elsewhere with arrows flying and mad chase scenes.

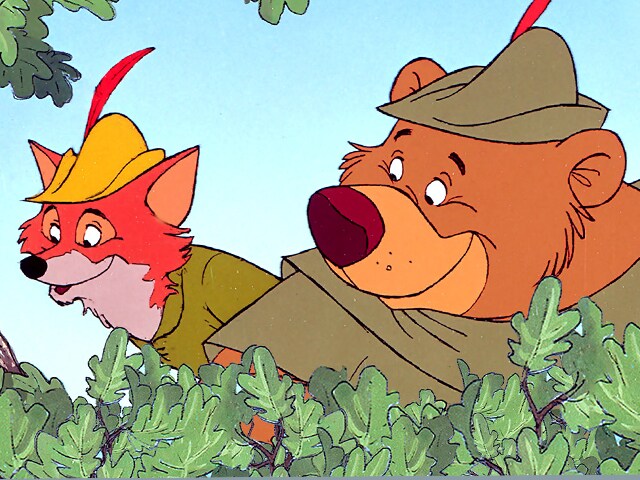

Robin Hood and Little John are certainly exceptions to the predator=bad/prey=good rule, but they have a particularly unusual antihero status which might explain those choices. Their moral virtues are established by further characterisation (such as in dialogue and musical themes), but even that in itself serves a moral purpose - we shouldn’t always judge a book by its cover, we never know what it might teach us unless we sit with it and try to understand what it’s saying. In the same way, we ought not to assume that a fox and a bear are inherently antagonistic, when in fact their moral code means they act for the community. Of course, there are ways in which this can be complicated if we think about the actual history behind the Robin Hood legend, namely the presentation of King John and King Richard I in popular culture, but the message is there all the same.

Community is a key theme in the story, where Robin Hood’s actions are for the benefit of the many, not the few, rejecting the greed of Prince John as he increases taxes on a whim and the cruelty of the Sheriff financially abusing local residents. The film isn’t exactly suggesting that hierarchy and division doesn’t exist in this setting, but that animals of different species might actually work together for mutually beneficial ends. Ultimately, whether this is actually true of the animal kingdom is beside the point - the film is depicting those relationships as a moral lesson about how working together can produce the best outcome for everyone in tough circumstances, and give us a sense of community.

Comments

Post a Comment