Howl's Moving Castle: Diana Wynne Jones and Hayao Miyazaki

Howl’s Moving Castle: Diana Wynne Jones and Studio Ghibli

Most people who’ve heard of Howl’s Moving Castle have never realised it was a book first, then a film. Now that I’ve both watched and read the story, the primary question that arises is: why did Studio Ghibli choose to adapt this particular story? Diana Wynne Jones’ novel has not much about it that suggests an affinity for Studio Ghibli aesthetics (although she does say she admired Studio Ghibli’s work for a long time before her novel was adapted). There are really a lot of differences between the book and the film which are quite significant to the original story, but they both still work as stories in their own right.

Let’s start with the basics. One version of Howl’s Moving Castle is a novel, and one is a film. That immediately creates some distance between the two stories because they’re working with different forms and techniques of storytelling and character- and world-building. For example, one of the big differences you notice between the film and novel is how central Sophie is as the story’s primary narrator, that is, how rarely we get any other perspective than hers in the novel, whereas in the film the camera gives us a wider view of the story and takes us away from just Sophie’s perspective to a more distant third person.

The Ghibli film allows the audience to have a broader view of the story and its characters, although our focus remains connected primarily to Sophie as she moves through the story. The novel privileges Sophie’s perspective, too, but doesn’t give the reader a sense of the wider world. In other words, our view of the story, its characters and its settings, is much more restricted in the novel because we’re following a particular character very closely, whereas there’s more freedom of movement in the film.

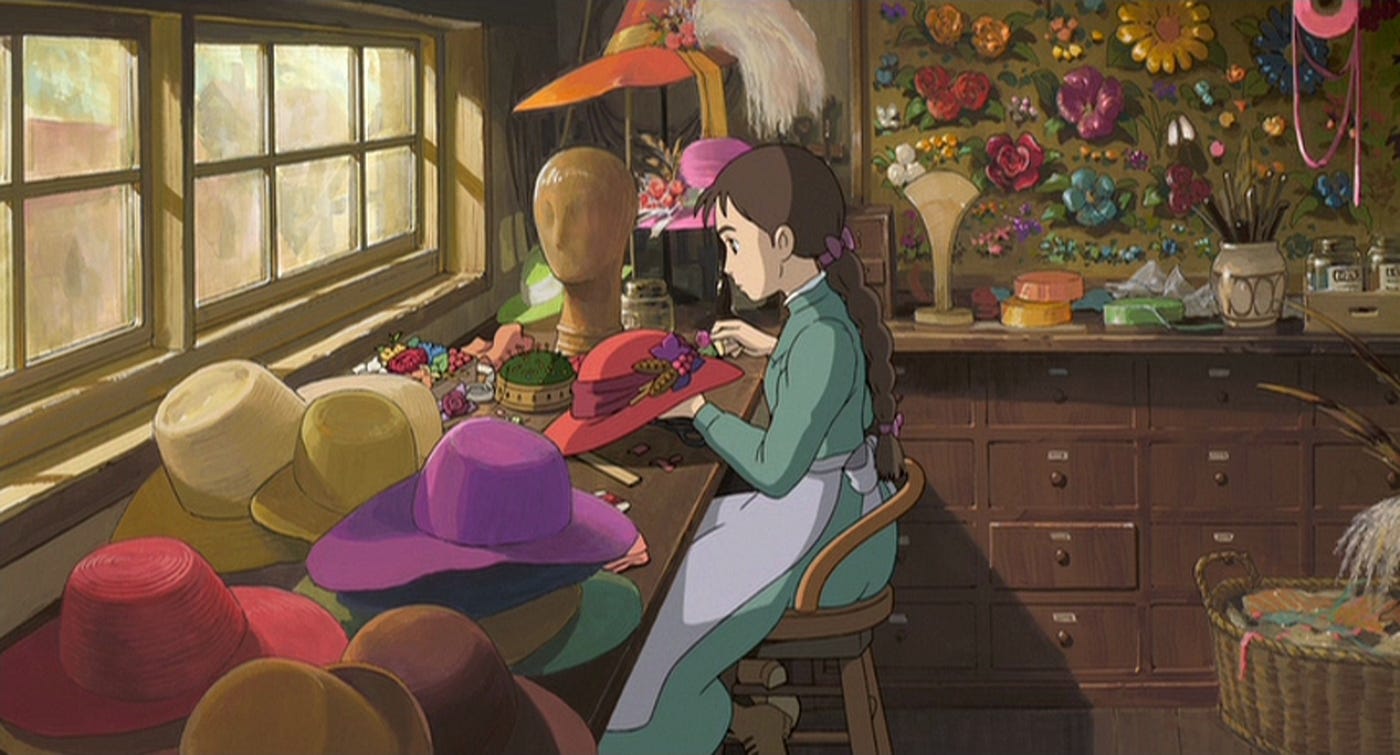

We do get a sense of Sophie’s inner thoughts and feelings in both the film and the novel, but in different ways. The novel relies on words to express an inner self; the opening chapter of the novel is called “Sophie talks to hats” and precisely demonstrates the use of words as a means of self-expression and communication - Sophie literally entertains herself by talking to the hats she’s making.

The film form, on the other hand, need not depend so heavily on words when meaning can be communicated by visual means like facial expressions or music. Partly it’s also in keeping with the style of Studio Ghibli that the film is generally a quiet one; Sophie doesn’t say much in the film, but we still do get a sense of her inner thoughts and feelings, whilst the novel quite literally tells us all those things. Sophie’s role as a narrator is just one of the many differences between the film and novel, but it’s an important point of difference because it can show us how different artforms can do the same thing in different ways.

All that, however, still doesn’t really answer that big “why?” question. Why did Studio Ghibli pick such a story for adaptation? Wynne Jones’ novel has quite sinister elements and themes, and her characters are much darker than their Ghibli counterparts. Is this adaptation purely an aesthetic opportunity?

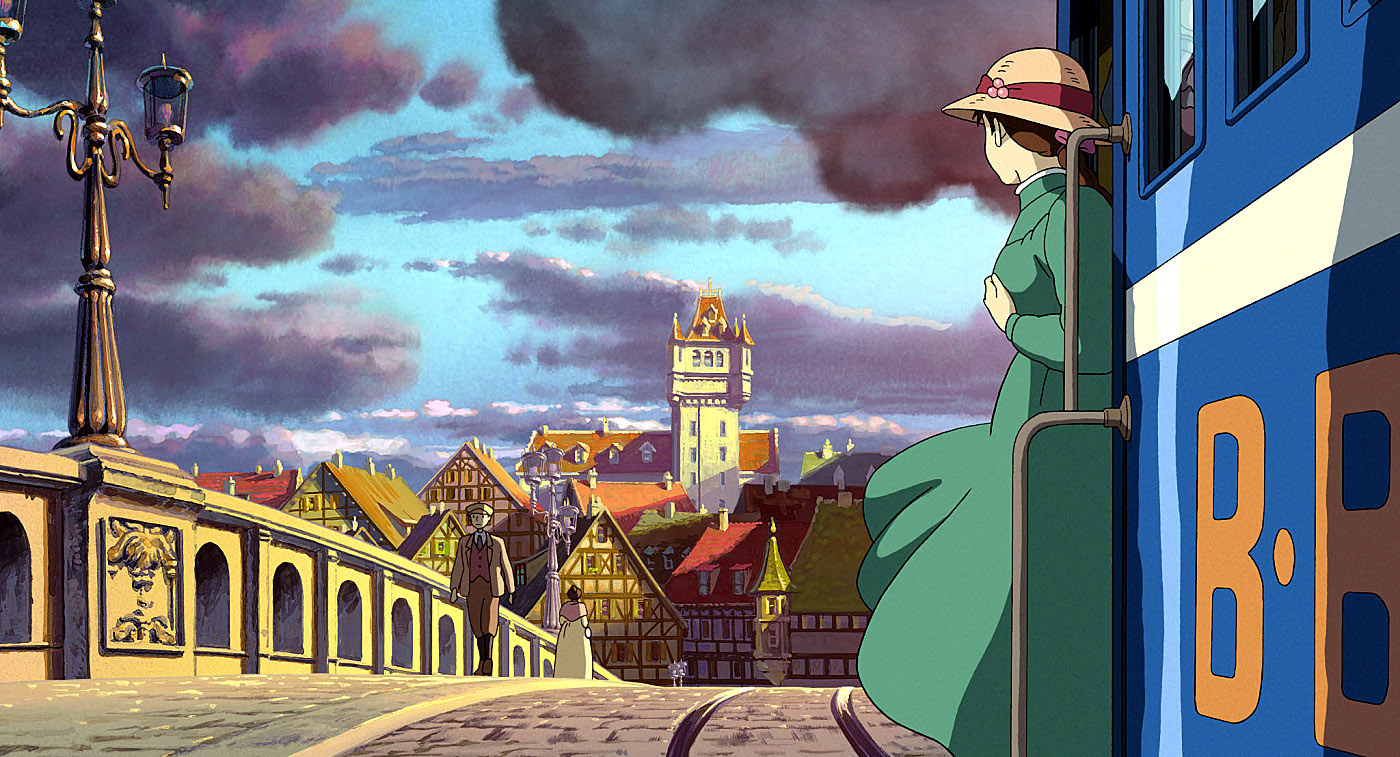

Studio Ghibli’s style emphasises the quotidian, romanticising life in all its ordinary beauty. We do have to remember that the processes of filmmaking and novel-writing are themselves very different, and that has a bearing on the end product. Joe Hisaishi’s score and Hayao Miyazaki’s animation and artistic teams come together to create a beautiful film, and Wynne Jones’ project of novel-writing produces a novel that is a great story in its own right, as well as a solid creative inspiration for Studio Ghibli’s film. Miyazaki’s film would quite literally not exist without Diana Wynne Jones’ novel in the first place.

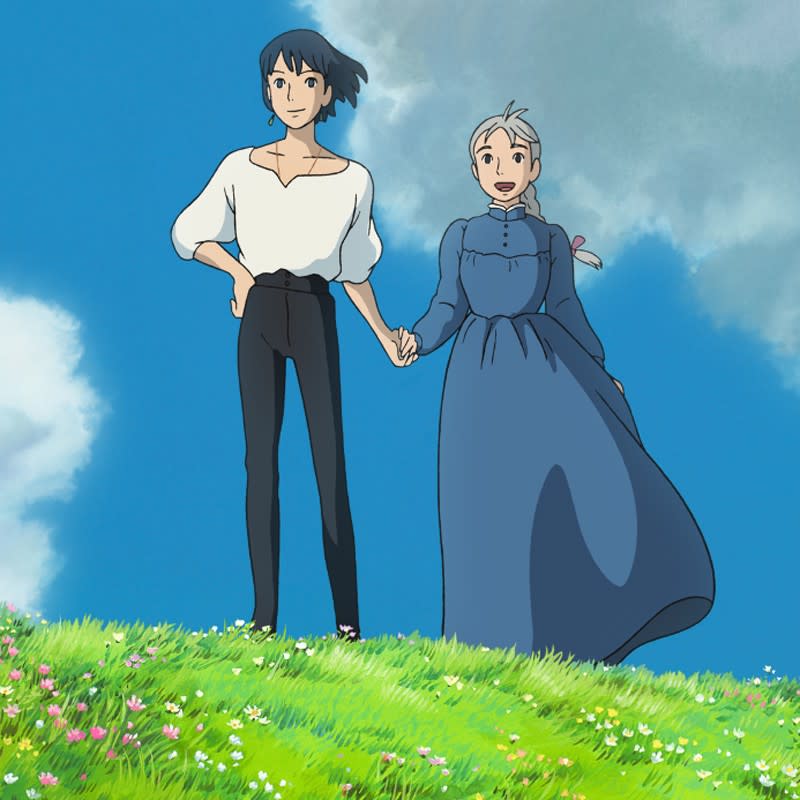

Wynne Jones has the opportunity to develop characters in great depth in her novel but there’s less room for that in this film (at least, for as many characters as Wynne Jones includes). Miyazaki reduces the story’s main cast in order to make the story more manageable and maintain a depth of character, and space for character development. More time is dedicated in the film to the hedonistic and aesthetically-oriented moments of joy, whereas the novel uses all its space to advance the story and give a strong sense of the characters and their world.

So why did Studio Ghibli decide they wanted to adapt Howl’s Moving Castle? It seems there was an opportunity to take a fully realised story and world and reframe it, prioritise different things, create a visual experience to accompany and complement Wynne Jones’ novel, and is that not what makes it beautiful?

Comments

Post a Comment