Blade Runner and Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?: human bodies

Blade Runner versus Do Androids Dream of Electric Sheep?: What makes a human?

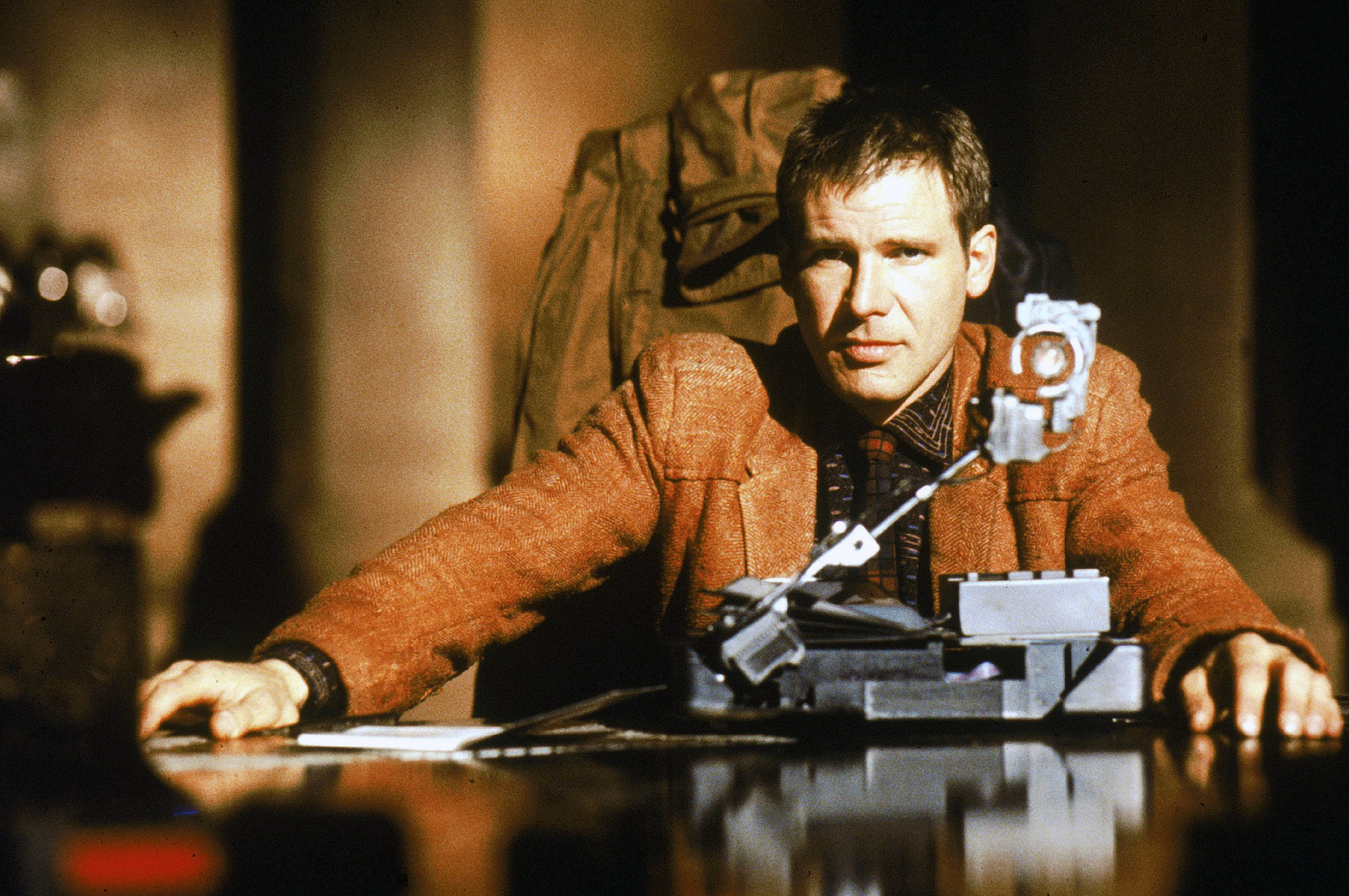

When we see actors on screen playing a particular role, I think we often forget that those actors are real people in their own rights. So when those actors, real people, appear on our screens pretending to be robots, how can we not be drawn in by the powerful sense of the uncanny?

At its core, Philip K. Dick’s 1968 novel and Ridley Scott’s 1982 film are both interested in how we define ‘human.’ Whilst in both the novel and the film, this has a lot to do with moral and ethical debate, it’s more obvious in Scott’s film that there is a visual element to these questions which is also very important. In brief, it’s telling an audience to look at a human actor on screen and ask them to believe not only that they’re performing a particular role but also believe they’re performing a non-human role.

And that distinction is intentionally complex and layered. Not just for the sake of making us question what we know within the world of the story, but for us to move on and question what we know of our own reality; to walk out of the cinema or finish the novel wondering if anyone around us actually is human, and what that in itself means.

Let’s start with the novel. On the one hand, reading characters off a page and being asked to conceptualise them from a literary description may make the lines between the human and non-human more difficult to distinguish because the characters lack the physicality afforded on screen. On the other hand, that lack of physicality may give us space to reflect on humanity in its moral and philosophical terms, not placing such an emphasis on the materiality of the ‘human’.

The characters exist only in our imaginations, and therefore how can they have any realism when they aren’t tangible bodies we can see before us, and have no voices we can hear? These questions bring us to something important in our assessment of the human: our senses. Can we see a human? Can we hear it? Can we touch it or smell it or, yes, taste it? Further than that, is the human now an ‘it’ because we’ve deconstructed our definitions so far that they become something entirely different? The questions spiral off into eternity.

All of this is conceptual, entirely in our heads, entirely the work of imagination. And yet, the same questions about the nature of humanity can be asked, with so little tangible material. Must the ‘human’ therefore have a definition and identity that is greater than a physical body? I can’t answer that question for myself, let alone for anyone else.

In any case, that’s largely the moral question Philip K. Dick poses to us: can an android, which by all means appears human, really be human? In my opinion, as much as Ridley Scott’s film is a fantastic visualisation and canny embodiment of the novel’s characters, perhaps it ought to be used more as a tool or supplement to the novel. The novel and the film both ask us to seriously consider what we understand ‘human’ and ‘humanity’ to mean, but whilst the novel asks us to strip away physical bodies or visual stimuli, those things make up a major part of the film’s substance. There’s no doubt that Scott’s film imagines the Blade Runner universe in a highly effective way, and the communication between characters is appropriately nuanced. It’s a very good adaptation for those reasons, but ultimately the novel form itself - specifically the novel’s request that the reader strip back physical sensations and suchlike - is actually more philosophically aligned with the story’s aims, interests, and questions.

Comments

Post a Comment