Why Didn't They Ask Evans?: Frankie and Bobby giving Poirot and Marple a run for their money

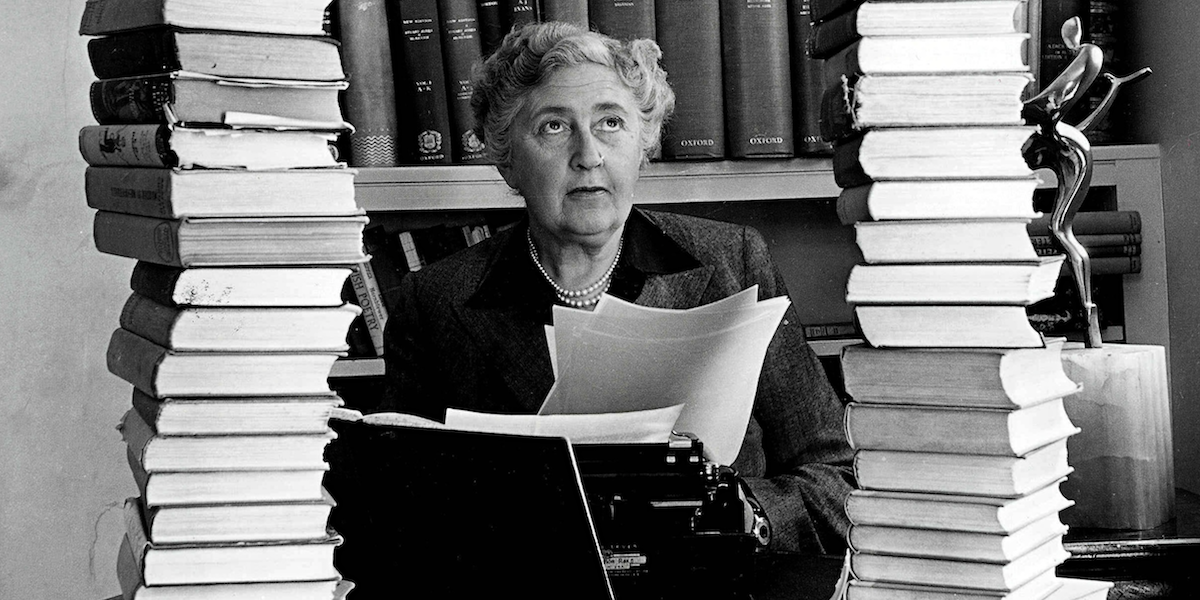

Why Didn’t They Ask Evans?: Agatha Christie’s literary talent

Everyone’s heard of Agatha Christie, and can almost certainly name one of her novels, if not many of them. Christie’s writing has come to be emblematic of the murder mystery, particularly within the time period she sets her stories. As such, it’s probably fair to say there is something of an Agatha Christie brand, if you like. Her work is recognisable and popular because it’s her work. People will read her novels because they’re written by her and therefore they must be at least half-decent. Don’t get me wrong, I love a good Agatha Christie mystery, but it should be said that there’s a difference between reading the works of an author you like, and reading the works of an author who is known to be “a good writer” simply because you have certain expectations.

I wonder if we’re used to approaching Christie’s work in relation to how it operates as part of a wider franchise and genre, so we place a lot of emphasis on solving the mystery rather than Christie’s writing as it sits on the page. (Perhaps an exception to this might be her play The Mousetrap which, being a play, makes Christie’s writing essential to the performance on stage, even though there are elements of creative licence that are always present when producing theatre.)

You don’t need me to tell you there’s a significant difference in the processes of watching a story unfold on screen and reading it on a page. Of course there’s also, I feel, a difference between reading a story then watching a screen adaptation, and watching an adaptation before reading the source text. Comparison is at the forefront of the mind, but this can also be seen in reverse: reading before watching can make us blinkered audiences. So the point is not that one method is superior to the other, but that either method has its own benefits and pitfalls, neither is perfect, neither is complete.

Hugh Laurie’s recent adaptation of Why Didn’t They Ask Evans? gave audiences a breath of fresh air after the past few years of heavy Kenneth Branagh Poirot adaptations (with another forecasted for release later this year). Frankie and Bobby are unconventional detectives, with all the enthusiasm of youth, a healthy dose of rebellion and sharp wits about them. They’re an excellent example of Christie’s ability to write characters not on the basis of mere description but through their dialogue and interpersonal relationships. Christie’s writing doesn’t rely on Lucy Boynton’s wry smile as Frankie or Will Poulter’s exasperated sigh as Bobby for readers to imagine those things in their mind’s eye. That’s part of the magic of Christie’s characters. But that being said, there’s something to be gained by watching Laurie’s adaptation and picking up on those little details in facial expressions and body language that contribute to the bigger picture. So yes, no particular method of reading or watching is perfect, or superior, but both in combination? Seems ideal, really.

This blog, then, is advocating for the work of Agatha Christie to be seen and read not just in relation to Hercule Poirot and Jane Marple. Those characters are iconic for a good reason, but they can overshadow the other great qualities of Christie’s writing. Christie is a great storyteller, and her writing style formulates characters through dialogue, rather than any lengthy 3rd person descriptions, but these things are lost on us if we only approach her work expecting Poirot or Marple. Novels like Why Didn’t They Ask Evans? and Murder Is Easy showcase Christie’s skills, and they don’t feature Poirot or Marple. I’d like to suggest that we take Agatha Christie’s stories on their own terms, not just as part of a franchise or brand.

Comments

Post a Comment