The Phantom of the Opera: the novel that should've been a play

One of the amazing things about adaptation is that it shows us how stories can work in so many different mediums. Whether you love The Phantom of the Opera or think it’s overrated (both valid opinions, we don’t judge here) there’s something to be noted in its success as a popular novel of its time, a hugely successful stage production, and an impressive film adaptation.

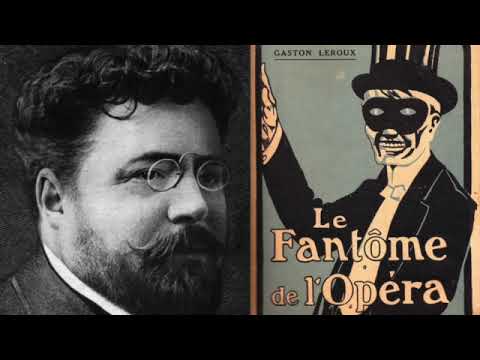

All of this success, it must be acknowledged, would be impossible without Gaston Leroux’s original 1902 novel, Le Fantôme de l'Opéra. As far as classic novels go, it’s probably not on most people’s reading lists, although I personally would very much recommend it. The novel isn’t particularly long, but it’s packed with action, and Leroux’s narrator is a very compelling storyteller.

So what’s so special and significant about the novel, and why does that make a difference in how it’s been adapted for stage and screen?

The story is, as the title suggests, interested in the Opera and by extension the theatre as a quasi-magical space. It really gives flight to the phrase ‘suspend your disbelief.’ The story is commenting on theatricality and performance as essential parts of life. Life’s many performances and illusions, Leroux seems to say, are reflected in the performances we might watch on a stage.

It seems Leroux wrote his novel anticipating a stage adaptation. So why not skip the novel and just write a play? I suppose that’s a question which could take up a whole other post, but my best guess lies in Leroux’s narration. In the Prologue and Epilogue of the novel, Leroux speaks directly to the reader and implores them to believe that the Opera Ghost truly existed, that he is not in fact mad, and that the story has come from verifiable sources who have had contact with the Ghost.

In the novel itself, a whole section of the narration is given to the character of The Persian, who tells the reader about his early exploits with the Phantom, Erik, and how he and Raoul eventually came to escape him. The novel form allows Leroux to talk directly to the reader without actually talking to them at all. It allows him to suggest verisimilitude, whilst giving the reader space to question, doubt, and critique everything he tells them. In other words, Leroux is determined to convince us his story is true, but at the end of the day, we’re receiving this story as a work of fiction - we expect it to be fictional.

And here’s where theatre and film adaptation become relevant. In the same way we approach novels with expectations of fictionality, so too do we approach stage and screen with expectations that what we see with our eyes is intended to be illusory. Actors perform particular roles in costumes and masks, make-up and wigs, sets and set pieces have been designed to trick us into thinking the spaces are real, and so on. Then, they do all of that again, because the story itself involves a theatre company putting on performances. It's a whirlwind of meta-theatricality. And yet part of this illusory experience is what makes theatre so special.

In a novel where the eponymous (anti-)hero is a man with apparently horrific physical deformities, sadistic tendencies toward violence, and yet the voice of an angel with a heart which yearns for love, it seems fitting that Leroux’s story has been translated into media where surfaces are merely illusions and the true interior self is much more difficult to discern.

Comments

Post a Comment